I vote for many reasons and one is because I was doing research a few years ago about the legendary soprano Leontyne Price and I got fascinated by the fact that she had been married. I hadn’t known that.

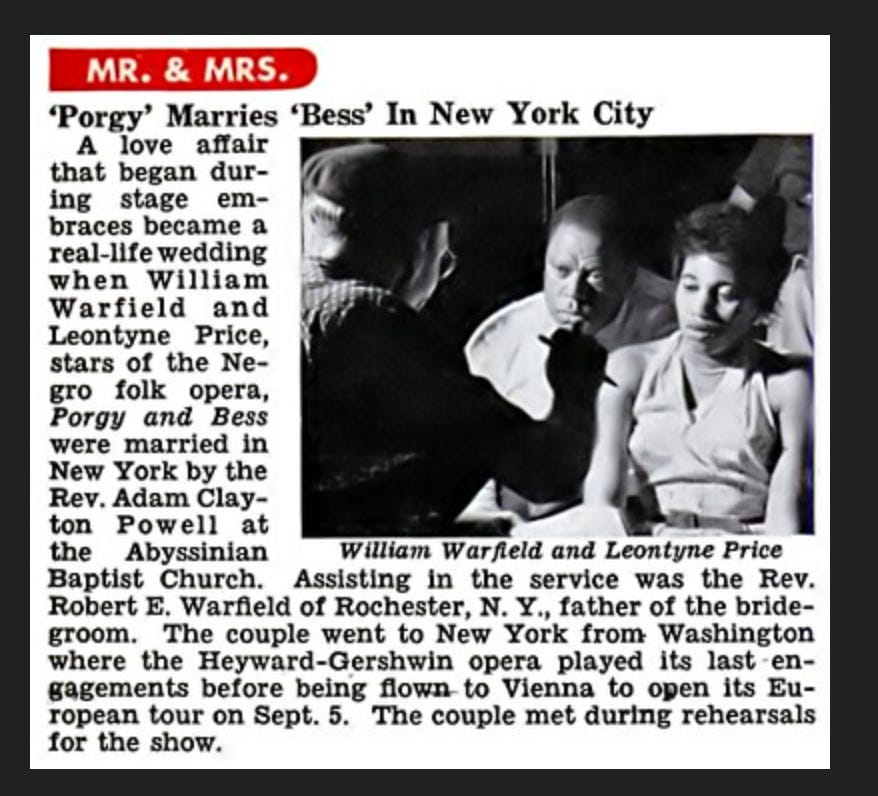

They were married in August of 1952. Price’s husband’s name was William Warfield, and he was quite the singer himself. I vote for many reasons, and one is because of the things that were happening around the time of he and Leontyne’s wedding. During strictly segregated times, Leontyne Price and her husband were both deeply creative and determined to win in a very white art form. Born in Arkansas, Warfield was raised in Rochester, New York, and performed with Price for many years. The marriage was short. But the relationship was long, snarly, and sophisticated.

When I’m researching, I tend to get obsessed by timelines and patterns and dot-connecting and what was going on at the same time another thing was going on. It’s context. I live for it — those situations that give the original situation more meaning. Context is missing in stories about Black artists. One of the reasons I vote is because I’m exhausted from our lives being bullet-pointed into “firsts.” It makes us hollow.

In a recent piece about ballet pioneers, I said

Black women’s lives are too often told in summary, or rushed through in well-intentioned biopics that, in a more equitably greenlit world, would be 10-episode documentary series. Promising books flatten quickly to literary curriculum vitae, complete with palatable headshots and the centering of “firsts”: first Black woman this; first Black woman that. These five ballerinas claim their share of what we so benignly call “breaking barriers,” but the slothful pace of “change” that weights so many of those firsts can tarnish a trophy before it’s home.

Yes: Price is the first Black singer to achieve an international reputation in opera. But being first is a jumping-off point. She’s — we’re — so much more whole than that. Price is related to Dionne Warwick and Whitney Houston, and her Mississippi life before opera is complex and picturesque and worthy of deep dive after deep dive after deep dive. I get way into it in my Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop. But still, it’s not enough.

I vote for many reasons and one is because the early 1950s were a scary time for Black couples who pushed the status quo. Just eight months before Leontyne and William tied the knot, many across the U.S. were protesting the assassinations of Florida NAACP registration activists Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette Moore. By the time of the Moores’ murder, Florida had the highest number of registered Black voters — over 100,000 — far more than any other Southern state. The Moores were at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. Victims of a terroristic attack on Black protest, Blacks voting, and Black love, their deaths made headlines nationwide. Harry was a school principal. Harriette was a teacher and insurance agent. They’d meet over a game of bid whist.

I vote for many reasons and one is because here was a bomb, you understand, and it was placed with diabolical precision under floor joists beneath Harriette and Harry’s bed. It exploded Christmas night at 10:21 p.m. “When those lights went out,” scholar Sonya Mallard said in 2020, “the klansman who was hiding in the grove waited, and then … crawled under the house, just like a snake.” Mallard is coordinator of the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Memorial Park and Museum, which sits on twelve acres in Mims, Florida.

I vote because Harry Moore died that night. Harriette Moore lasted nine more days. I vote because after years of working with her husband at the battlefronts — lynching protests, voter registration, and standing up for Black people falsely accused of crimes — Harriette was tired. “There isn’t much left to fight for,” she is reported to have said from her deathbed. “My home is wrecked. My children are grown up. They don’t need me. Others can carry on.”

I vote because the 1951 Christmas bombing that ended their lives was also the twenty-fifth anniversary of their wedding.

In 2005, as he prepared to run for governor, Florida Attorney General Charlie Crist reopened the investigation of the Moore murders, relying mostly on the extensive FBI file. He named four klansmen, all long dead, as the murderers.

Too little. Too late.

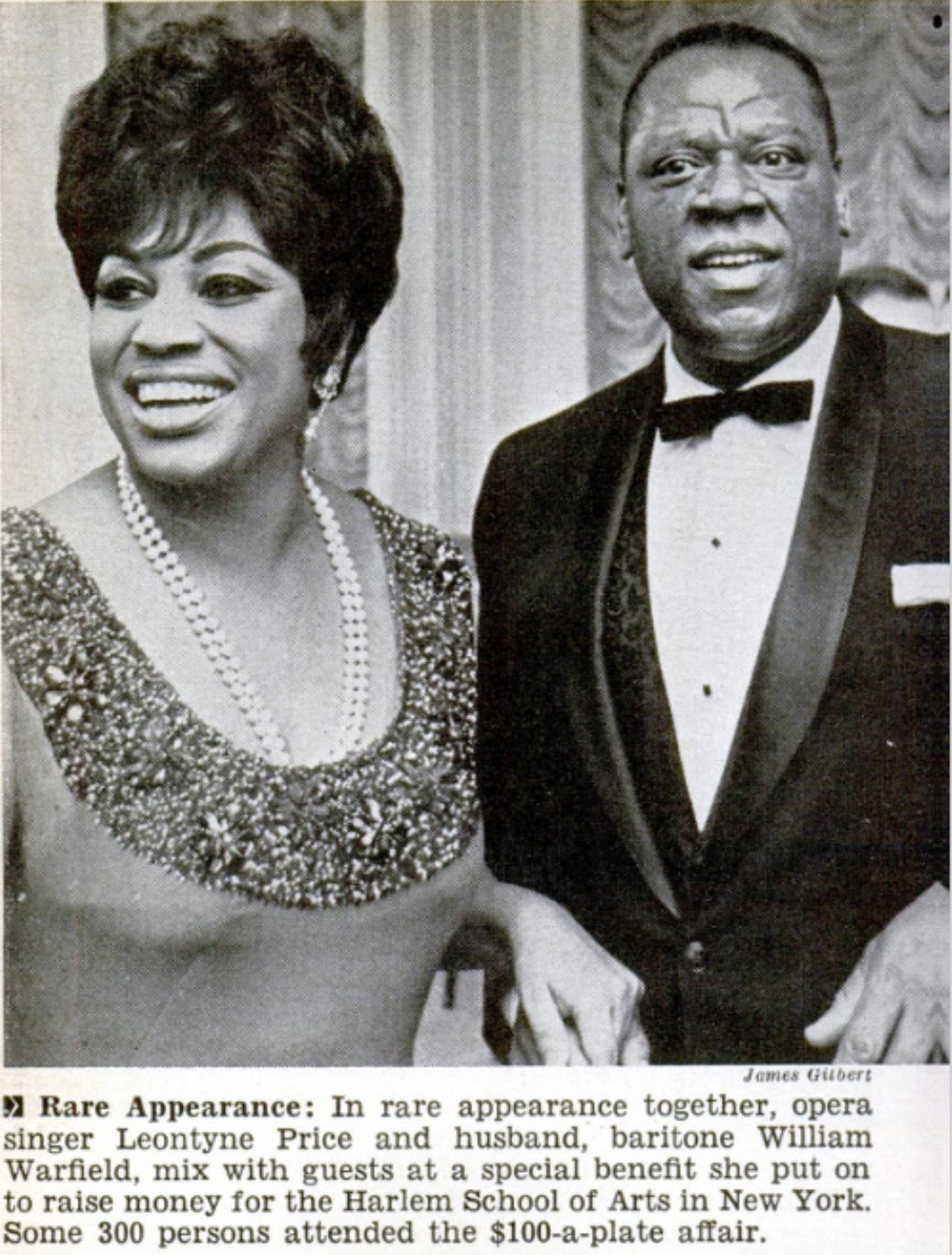

Leontyne went on to become Leontyne. Warfield enjoyed success but didn’t make it quite as far. Over the decades, he made his living as a recitalist, an occasional actor, and in 1984 won a Grammy in the Spoken Word category. Warfield would never escape “Ol’ Man River,” though—a Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein song made famous by Paul Robeson. They performed it years apart in the problematic musical, Showboat.

Let me go ’way from the Mississippi / Let me go ’way from de white man boss / Show me dat stream called de river Jordan / Dat’s de ol’ stream dat I long to cross. I vote because even when Warfield and Robeson’s performances rise to beauty, it’s an awful song to sing soulfully in front of white people, over and over and over again.

“There’s a sadness to it,” Warfield said in 2000. “Sometimes it’s…laid-back, and sometimes it’s even angry. The most difficult time I had with it was singing it just four days after Martin Luther King’s assassination…. I had to hold back my emotion…to keep from breaking down altogether.” It was especially cruel, as Warfield was rarely allowed to work in opera, the profession he loved, had trained for, and at which he excelled.

Price and Warfield divorced in 1972, having been legally separated since 1967—and actually separated since 1959. There were no children, and the duo apparently worked together cordially over the course of those years. Warfield, it is said, blamed “career issues.” Almost everything written about their divorce, if it warrants more than a mention of the date, says it was the couple’s “busy careers” that led to the end of the marriage. Perhaps it was.

As I said, I vote for many reasons, and one is because I knew so little about Leontyne Price beyond her being a first, I hadn’t even known she was married. I vote for Harriette and Harry and what had to be a profoundly romantic game of whist. I also vote because we are the others that Harriette said could carry on.

In music,

Danyel